The Challenges Of Modern Street Photography - An Interview With Daniel Valledor

The Spanish artist has wandered and documented the streets of Madrid for more than 6 years now. His unique image language and dedication to the process have earned him the attention and respect of a growing crowd, including brands such as Leica. In 2021 his book on the streets of Madrid will be out after more than half a decade of preparation. We had the pleasure to talk to Valledor.

Daniel, your photography separates strongly from modern commercial or fashion photography. How did you first get in touch with the craft and which choices helped you find your path?

My initial relation with photography began right after college, and was directly connected with cinematography, meaning it was all about understanding how light could be used to tell a story better. So it was a "narrative relation". The problem about this is that it requires a lot of prior planning and both human and economic resources, which kills any visceral attempt to use photography. That's why I started shooting the street and everything that surrounded me: every time I walk out the door, a new adventure begins. And that's all you really need: a camera, two feet and a little bit of grit.

There are a lot of great cinematographers, any specific ones that stand out for you?

I admire the all-time great cinematographers, like Vittorio Storaro, Gordon Willis or guys still hitting hard to this day, like Roger Deakins. Those are fantastic visual narrators. But the people that have really inspired me on the street photography side would be the Spanish photographers from the 20th century: Ramon Masats, Catalá-Roca or Joan Colom. I still see their essence or whatever I believe drove them whenever I walk down the streets of Madrid.

Technology has changed the art of photography because...

...it has been taken for granted. Before phones could provide any usable images, the process of documenting with images required some prior intention. This is precisely the reason why I don't shoot digital anymore: finite resources usually demand better decisions. Every click is the result of your decision to capture a certain moment and not the other one instants away. Digital photography definitely got rid of that limitation. Even though this was actually a good thing (more liberty), I believe it has backfired to a point where I personally couldn't tell between what made sense and what didn't anymore. I guess I got to a point where I found myself blasting pictures in burst mode just to capture a specific moment, sort of trying to "cheat" time somehow, and this made me rethink my entire process.

Would you say street photography is easier in this day and age than it was in its peak years decades ago?

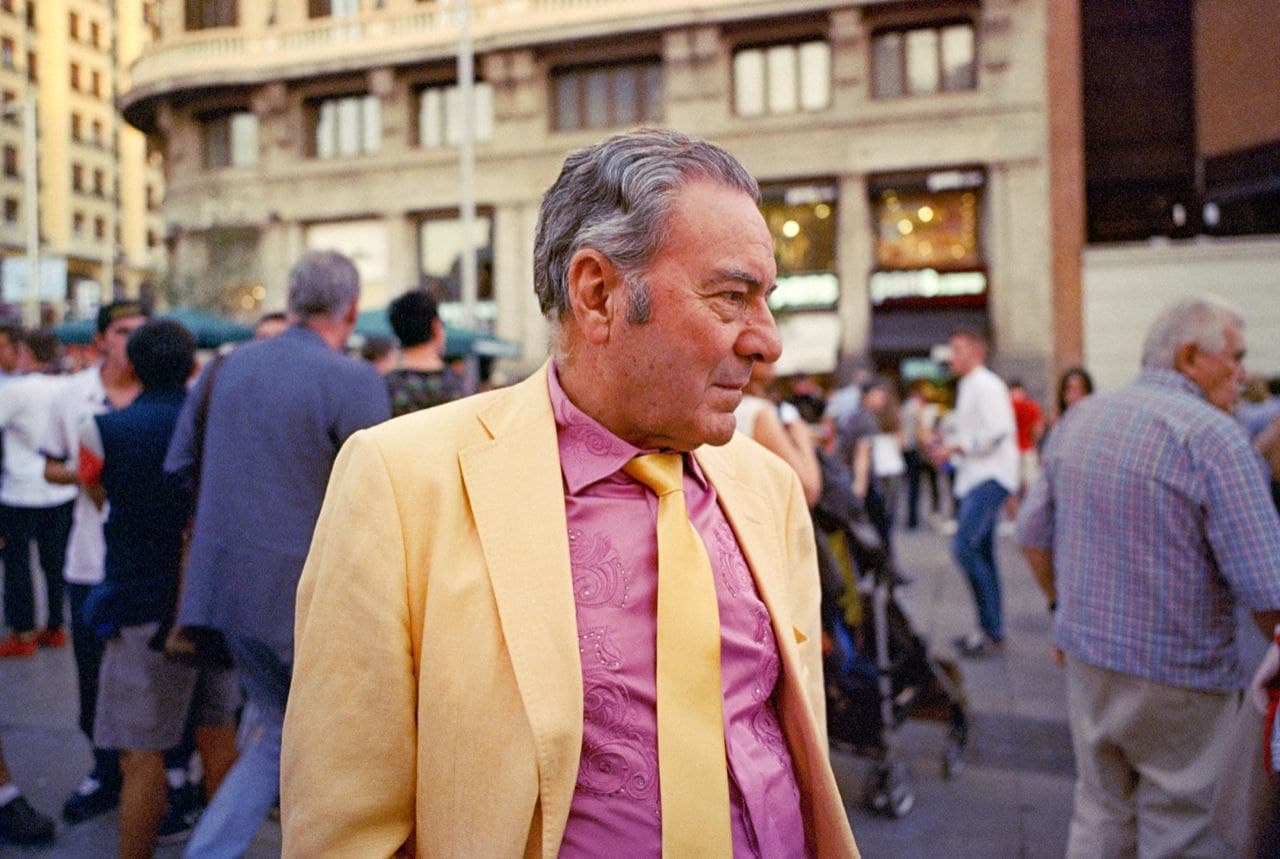

In my opinion, shooting street photography has never been harder than it is today, even though I obviously haven't lived through the 60's or 70's. But from an aesthetic standpoint, there used to be enormous coherence in industrial design (cars, streetlights, etc.) and clothing. Everything was so visually balanced, even the worse car or the ugliest clothes. Today everything is so eclectic that even if they're not bad designs on their own, radically different design concepts can be disastrous when put together in a same scene. Think about a North Face neon-green-colored jacket for example. They're pretty cool, aren't they? Yes, but anyone wearing that in your photo will definitely ruin it. And that's just the aesthetic part. Bruce Gilden said that as the years have passed, he could see how everyone was starting to look the same. I agree with this completely. A very eclectic society can be good in some aspects, but when people blend into a mixture of everything, what stands out is usually nothing.

About your upcoming book, what makes it different or worthy over everything else that is already being published on street photography?

Well, I honestly think that's for the readers to determine. All I know is that I've tried to be as honest as I could when depicting the scenes in the book, meaning that I would only capture what actually interested me, without thinking "this will make a great photo". In fact, most of the times I happened to be wrong and 99% of the time the captures got discarded because there was nothing interesting in them. The process is the result of more than six years of wandering about the same streets. I assumed the shooting process to a point where I didn't notice I was carrying a camera with me. If I saw something interesting, the process of clicking was an unconscious reaction. Then it would be a memory buried in that film roll that could take weeks for me to re-discover I ever recorded it.

Thank you very much for you interesting insights, we appreciate you taking your time. Let's finish this beautiful conversation with this sentence:

For Daniel Valledor, photography is... ...an escape valve.

* This is a contributed article and this content does not necessarily represent the views of enstarz.com